At around three o’clock in the morning the ICU staff hurried my dad, confined to a stretcher under a web of wiring and tubes, to emergency surgery. My family was unreachable, leaving me alone and distraught in the ICU waiting area. In the main seating room, a wall-mounted television played the news on a loop, pushing me into a quieter alcove out of reach from the churn of the world.

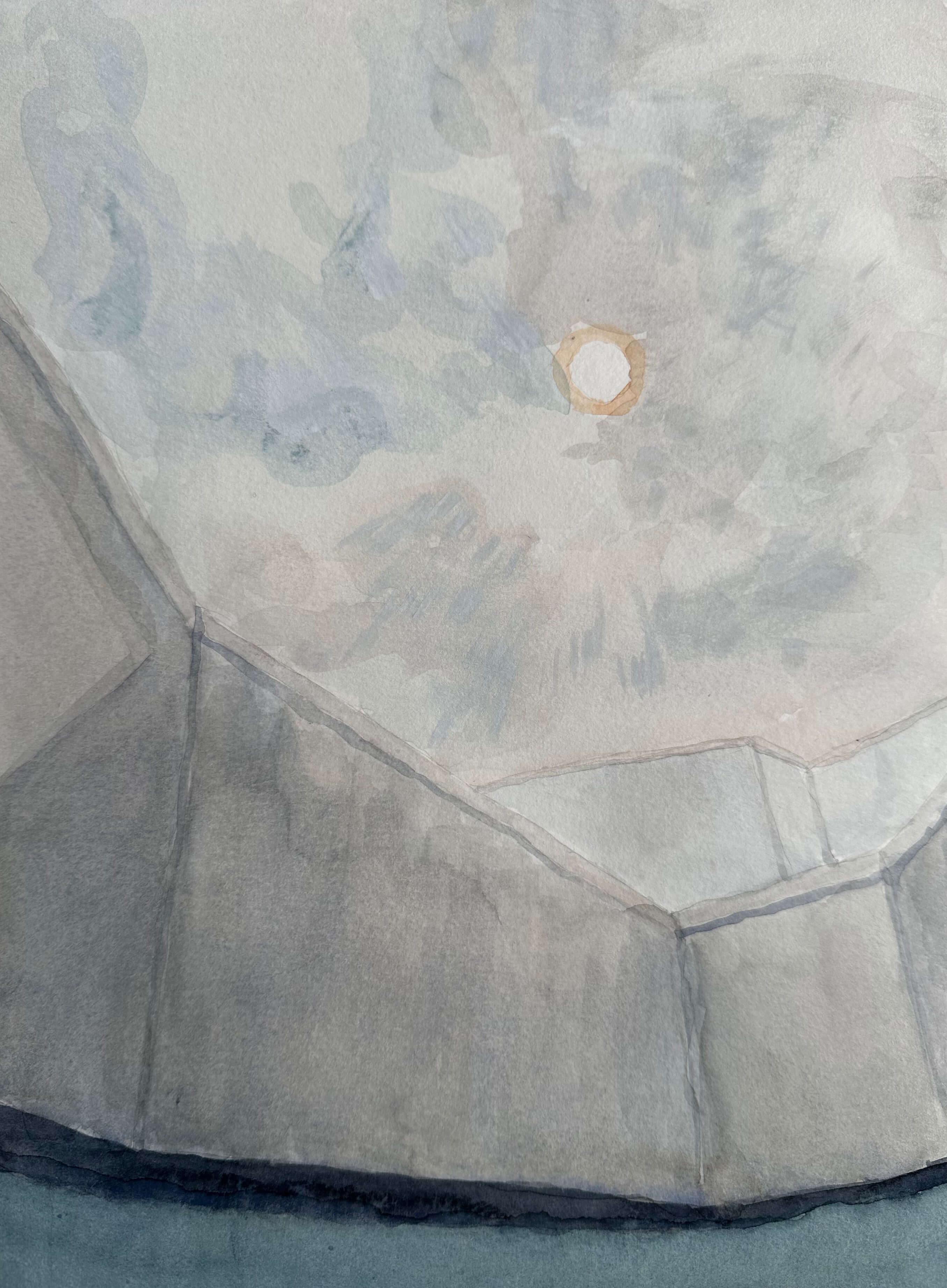

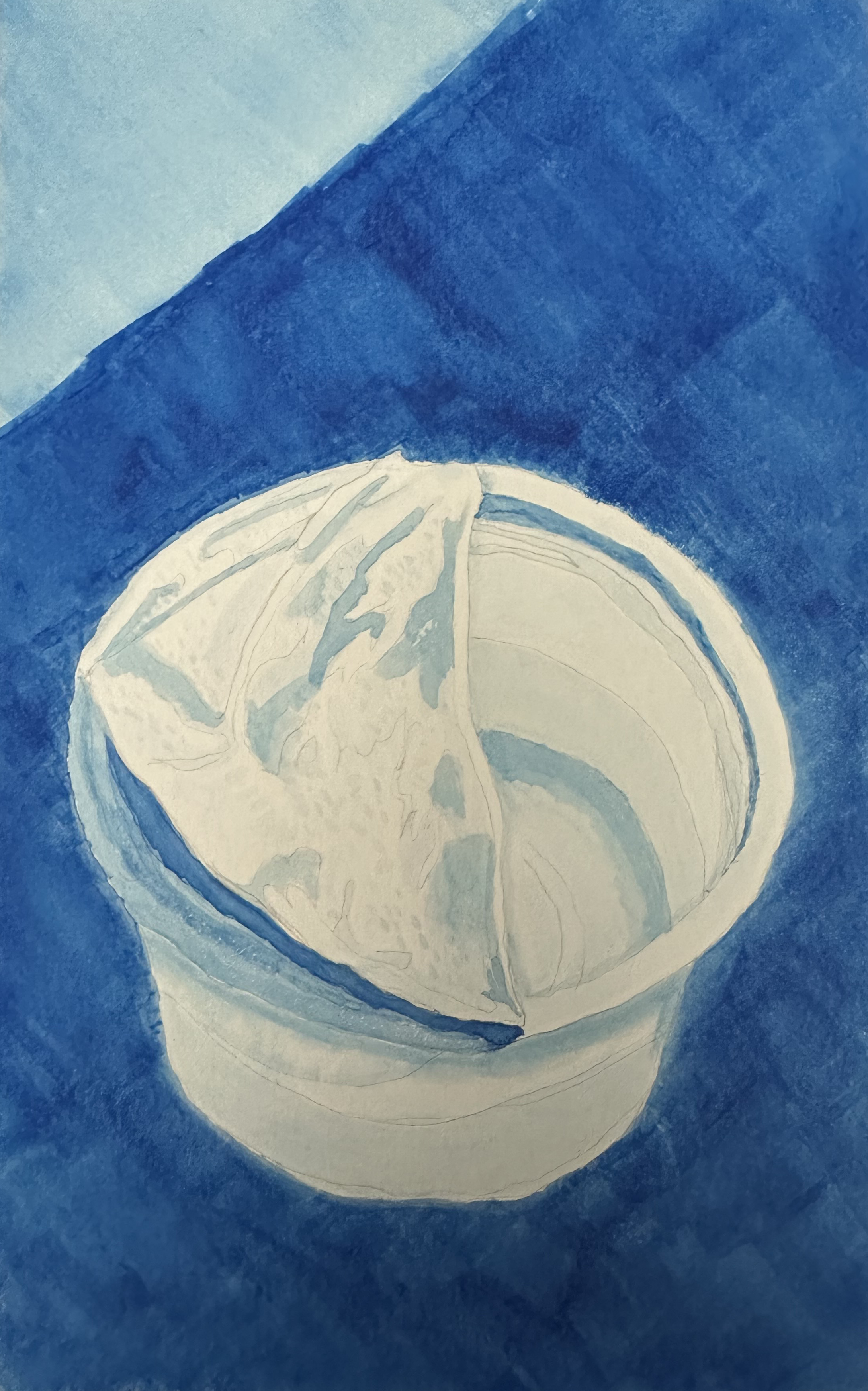

This secluded space was where my family preferred to sit when deployed to the waiting area, facing a blank wall guarded by a folding table adorned with just one pot of sunflowers. There were skylights in the waiting area, so I presumed the sunflowers were real, though I don’t remember smelling them to check. I sat on the table instead of the chairs, close enough to the glass entrance so that the doctors could still see me from the corridor.

Earlier in the night my dad had suffered a cardiac arrest while I was home in bed. A nurse was able to resuscitate him but by the time I arrived frantically, the on-call surgeon told me bluntly that he was still “bleeding to death”, requiring surgery that the anaesthesiologist’s body language implied was perilous. So I surveyed the lonely sunflowers while I waited and contemplated death – and what we do while waiting for it to arrive.

It occurred to me that in dad’s time at the hospital, very little of my waiting actually occurred in the designated ICU waiting room. Instead of enduring its worn-out chairs and its coercion to publicly brave your pain, I often preferred to wait in a service corridor with a direct view to the ICU’s front door. Even though it doubled as a makeshift storage area for broken equipment, I preferred it to the waiting room because it was more private, had windows to a courtyard and was closer to my dad, which somewhat calmed my nerves. Waiting here felt like a small act of defiance – a way to take back control.

Ironically, I had spent over a decade working in hospitals and studying their architecture to only now feel the full weight of their authority. Hospitals are among the most strictly programmed buildings we design. Within a hospital, I would argue that the most strictly programmed space is the ICU. Its design is a logistical triumph. It is hyper-optimized. Machines, drugs, data and staff all coordinated to keep bodies alive at the edge of death.

Yet the gravitational pull of my dad’s ICU bed was inescapable. While waiting by his bedside, my dread was uncontrollable. In the ICU, time slowed down and its systems of control could not inhibit my suspicion that they were functioning on a protocol that I wanted to reject – optimized for probabilities, not for hope.

Waiting, however, cannot be optimized. Any measurement of waiting is inadequate. So only its experience revealed to me the chasm between what our modern systems are designed to optimize and what we are forced to endure within them. But as painful as this experience was, it was waiting that suspended me from the pace of these logistical systems and allowed me time to reflect on their emotional incapacity. Or perhaps their emotional obfuscation suppressing our fears of losing control.

Months after my family’s time in the hospital, I enrolled in several art courses at OCAD University as a part of my healing process from the trauma of the ICU. The most significant for me was a certificate course focused on empathy and ethnographic research in design, taught by Nadine Hare and Renn Scott.

The course led me to Dana Cuff, Professor of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA, who contrasts anthropological fieldwork, which is interested in human interactions and ethnographic accounts, with the shallow “site visits” performed by professional architects. It also led me to Arturo Escobar, Professor of Anthropology at UNC Chapel Hill, who has written on the relationship between ethnography and design, and argues that ethnography helps designers dispel the idea that space is just a neutral container, rather than something created through our relationships. If, instead, we are immersed in a “network of interactions”, as Escobar puts it, then we are all, in some sense, designers – co-creating the world together. I raise this digression because my final project for the course, an ethnographic inquiry into family experiences of waiting in the ICU, became a way for me to make sense of my time in the hospital.

For instance, my preference of waiting in the neglected service corridor revealed a deeper network of interactions than just a superficial reading of proximity, unlike the way a conventional architect might analyze a problem prioritizing linear measurements of distance between fixed points. I wanted a clear view of the ICU entrance, driven by a fear that the staff might otherwise avoid my gaze. I positioned myself in a location that afforded eye contact with the staff so that I might be able to glean more information from them as to my dad’s status. Also, I felt I might be able to impart more control over them with eye contact as if to say: “I’m watching your every move, so you better make sure my dad gets better”.

My interactions with other people in the ICU waiting room also influenced my movements. One woman waiting on her comatose mother approached me in a paranoid frenzy, offering unsolicited stories on the trustworthiness of the ICU staff. Like a mirror to my own paranoia, this event triggered me to shield my own fragile mother from this stranger’s negativity.

Again, I yearned for control over the flow of information and created a world where, regardless of the veracity of this woman’s claims, my mother’s positive headspace took priority. What kept me out of the waiting room was not the space itself, but my entanglement with a stranger, my mom, my dad and his caregivers. From these interactions emerged socio-spatial relationships more complex than could be controlled by simple design parameters of, say, the number of chairs that could fit, or the colour of the walls.

And yet, as my dad’s health declined, one fleeting interaction I experienced was meaningful. The main hallway outside of the waiting room widened at a nexus of routes via service elevator, cafeteria staircase, parking bridge and ICU. Here I crossed paths with the son of another ICU patient who nodded to me silently. The ambiguity of the space allowed for sincerity to emerge.

Using ethnographic methods I could describe my family’s hospital journey within a gradient of control, back and forth across four adjacent and distinctly programmed spaces: waiting room, main hallway, service hallway and ICU. We moved ourselves from spaces where we felt powerless without control, towards spaces where autonomy afforded an impression of control. This was me in the service corridor, defying instructions to sit in the waiting room. This was me sitting on top of a table, instead of in a chair.

Implicit in these stories is hierarchy. Margaret Waltz, in her ethnography of medical waiting rooms, describes waiting as a “manifestation of power relations”. Who waits for whom reveals the hierarchy. Those whose time is the most valuable wait the least – and have the greatest power to shape the conduct of others. In the ICU, doctors crowned this time hierarchy, followed by nurses, patients, and finally families. The complexity of modern healthcare may require hierarchy to function efficiently, yet its bureaucratic inefficiencies accumulate in waiting.

We waited for medical staff – not the reverse. For x-ray technicians to return from vacation. For a doctor to finish a round of golf. Which is not to say that hospital workers do not need breaks. This is not an indictment of healthcare professionals that I greatly respect. It’s clear the different value of their time comes down to accounting – there are fewer of them than there are of us. But when my dad was on the precipice of death, there was no surplus time for me to take a break.

Staff would often urge me to go home to get a good night’s sleep. I didn’t want to. I wanted to stay in the hospital close to my dad. When I was at home in bed the night of his cardiac arrest, I wasn’t even sleeping. The architects of the hospital didn’t design a bedroom or a shower for me, so my choices were foreclosed.

Perhaps the architects should crown this time hierarchy. They have the power to preclude and they also disappear once the hospital is built. The normative definition of an architect’s responsibilities provides an alibi for resisting immersion in a network of interactions. The limit of their professional scope is the realization of an object frozen at a fixed point in time – in subservience to Chronos. But waiting revealed to me that time is not universally constant. Time is a musician: it warps and weaves around us, responding to us even as it acts upon us. Sometimes it turns on a dime – from a dance to a dirge.

The time had come for dad to breathe on his own, off of the ventilator. And these would be his last breaths. The latest on-call doctor wanted to know when we were going to arrive at the ICU to say goodbye. Earlier, this same doctor brought my mom to tears when he mechanically told her he was a “man of statistics, not of hope”. Even now, this memory tightens something in my chest.

Our previous on-call doctor was warm and caring by comparison, fighting for my dad in dissent from the hospital’s bureaucracies. Instead, the latest on-call doctor was the one who coldly interpreted my dad’s brainscans. He also embodied hierarchy as he marshalled the ICU under his control. The nurses were openly intimidated by him. When this clockwork-doctor commanded orders, this was undeniably his ICU. Morning rounds began promptly at 10:00am and, true to form, were conducted from his computer workstation-on-wheels in a clockwise direction around the central nursing station. Under his reign, the ICU became an actual clock. Waiting for the doctor to count his way down to us with dad’s brainscans was the slowest time of my life.

Yet afterwards, for the first time in our two weeks of waiting, it was the system that needed our input. The clockwork-doctor now had to wait for our decision.

After my brother and I decided wrenchingly to let dad breathe on his own – mom couldn’t bear to be involved nor interact with the clockwork-doctor – our family went to the hospital ahead of schedule the next morning. Our disregard wasn’t willful as we had relayed a message for the doctor. When I found out later that the clockwork-doctor was upset because he was not informed of our change in arrival time, I must admit to extracting a sliver of gratification.

When my dad was still conscious the week prior, the last words he uttered exhaustedly to me were: “who’s driving this bus?” Fighting back tears of frustration, I replied that I was driving the bus. Today, when flashes of anger combust inside me, I channel this memory as a promise to my dad to wrest control from the forces that seek to dominate and divide me. Yet in my moments of calm, I wonder if this narcissistic rage misses the point of a deeper lesson. Did my dad’s last words serve a more introspective, Socratic purpose?

Who indeed is driving this bus? Despite hierarchical machinations, it’s not any one person or force. It’s a network of interactions from which forces emerge. Except with all of our hands on the steering wheel, none of us can be completely certain which way the bus will go. Like a Ouija board planchette, the wheel appears to turn on its own. And fearfully, control becomes our remedy for an uncertain future. Quantified time displaces presence, with care becoming optimized in priority of the future – not for those who must wait now. From this displacement an asymmetrical misalignment grows between a technical idea of care and an emotional one.

Is a redefinition or redistribution of care possible? Margaret Waltz’s dissertation implies that families and patients should be cared for together, but that they are segmented when care is reduced to merely technical solutions. She posits that care could be improved by shifting from bureaucratic efficiencies towards a moral theory known as “care ethics”. It broadens the scope of care beyond individuals to include others in a relational interdependency more sympathetic to emotions. This again invokes Escobar’s network of interactions. Drawing upon an ethics of care would help us preserve the entanglement of relationships that technical systems seek to segment into data points.

An ICU is one such technical system in the worldview of modernism. As a logistical triumph, it’s both an apotheosis and a nadir of modern architecture. If we are to mediate care, situate new ethical responsibilities and resist systematic control, then perhaps it should start here. On the precipice of entropy – death’s door.

Here, sitting on a waiting room table at around three o’clock in the morning is where I waited and contemplated what to do. What does it mean to act in the first instance, so that we don’t reproduce this ordering – this architecture rooted in control of that which it cannot control? How can we acknowledge death?

I don’t think modern architecture properly acknowledges death. I’ve learned that waiting and death are both unconstrained by modern architecture. They persist beyond the walls of the hospital. Much modern architecture seeks to obfuscate their evasion. Much modern architecture is subservient to Chronos. But waiting is a non-programmed liminal space – between life and death. Waiting is revelatory – a form of Kairos: the seizing of a moment that occurs within the flow of Chronos. After waiting patiently it breaks through in a single, transformative moment of change. It points to an opportune time for action, not action all the time. Not moving fast and breaking things.

In the immediacy of my dad’s death, I raged against Chronos. It was too fast. Too inopportune. Dad’s illness was unexpected and his descent sudden. But through this journey, Kairos may have emerged, unshackling me from Chronos to teach what care could be.

I resigned from my job as an architect to care for my mom; for relationships. I’m still waiting now, but on my own time.